Fair Pay in Principle, Unfair in Practice

The government’s plan for a Fair Pay Agreement in adult social care sounds fair in principle. After years of underfunding and instability, few would disagree that care workers deserve better pay, recognition, and security. But the challenge lies in how it’s applied. A single national agreement, imposed on a sector as varied as social care, risks creating new problems for the small, independent providers who deliver most frontline care.

The government’s consultation describes adult social care as a “sector,” as though it functions like one large, structured organisation, something comparable to the NHS. That language matters because it shapes how policy is designed.

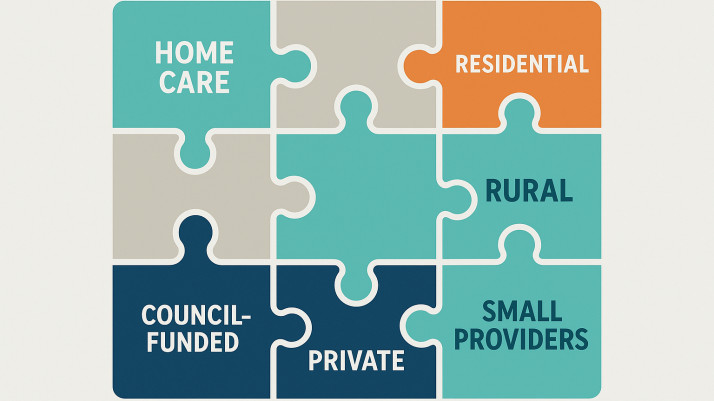

Unlike the NHS, social care isn’t a single organisation with a central budget or unified management. It is a patchwork of thousands of independent providers, from large national companies to small, often family-run local services. The government’s Fair Pay Agreement proposals would introduce some structure, with employer and worker representatives negotiating national pay and conditions. But it's still unclear who will represent small providers at that table or how any agreed pay increase would be funded.

When NHS pay rises are agreed upon nationally, the Treasury and the Department of Health can negotiate directly on funding. In social care, there is no such safety net. When costs go up, providers are expected to absorb them immediately, often without any increase in the hourly rates paid by councils or private clients.

So when the government talks about a Fair Pay Agreement “for the sector,” it overlooks a basic reality. There is no single financial system or central funding flow. The term “sector” hides the complexity and the vulnerability of the independent care market.

Who will speak for small providers?

Under the current proposal, the Fair Pay Agreement would be negotiated between worker representatives (unions) and employer representatives. On paper, that sounds balanced. But in practice, it raises a serious question: who will represent small, independent providers?

Large national organisations and umbrella bodies are likely to dominate the employer side of the table. They have experienced negotiators, lobbying power, and the capacity to attend regular consultations. Small providers, who make up the majority of care businesses in the UK, rarely have that kind of voice.

We are not opposed to negotiation, in fact, most small providers would welcome being part of a constructive national conversation about pay and standards. But if those negotiations are led only by large organisations, the resulting agreement risks being shaped around their priorities: dense urban coverage, high volume contracts, and centralised management systems. That’s not the reality for small community-based providers who operate with lean structures and personal accountability.

Most care in England isn’t delivered by national chains; it’s delivered by hundreds of small and medium-sized providers embedded in their communities. These services run on tight margins, with local management and minimal overheads. They don’t have HR teams, financial buffers, or diversified income streams to spread risk.

Providers working in more affluent areas, with a higher proportion of private clients, may be able to absorb wage increases more easily by adjusting their fees. But those operating in areas of deprivation, where most care is funded by local authorities, simply cannot. The result would be an even greater divide between regions, with care availability determined not by need, but by postcode.

A national pay floor agreed through an FPA would almost certainly raise wages, which carers deserve, but without guaranteed matched funding, small providers won’t be able to absorb the increase. Larger organisations may weather it through economies of scale or private-pay clients. Smaller ones, particularly those reliant on local authority contracts, may not.

The result is that we lose small, independent providers and are left with a handful of large national organisations dominating the market.

The rural reality

Nowhere is this imbalance clearer than in rural areas. A provider covering 40 or 50 miles of countryside faces high travel costs, low client density, and long unpaid journeys between visits. Local authority rates rarely account for that.

A Fair Pay Agreement based on a national average would ignore these structural differences, placing rural services under even greater pressure. The intent may be fair pay, but the outcome could be reduced availability of care in the places that need it most.

Introducing a national pay negotiation framework would come with its own cost. It would require administration, oversight, data systems, and enforcement, all of which draw resources away from the frontline. Yet the solution is far simpler: fund care properly. If local authorities were given realistic rates that reflect the true cost of care, providers could pay their staff fairly without the need for another layer of national bureaucracy.

No one disputes that care workers should earn more. But fair pay cannot exist without fair funding. Unless commissioning rates rise in line with wage increases, many small providers will face an impossible choice: absorb the loss, reduce visits, or hand contracts back.

If that happens, the people who lose out aren’t just employers, they’re clients, families and communities who depend on continuity and trust.

The Fair Pay Agreement could be a landmark step for social care but only if it reflects the real diversity of the sector. That means recognising that fairness isn’t about uniformity. It’s about understanding the context in which providers operate and ensuring that funding, expectations, and representation are aligned. Without that, we risk creating a policy that’s fair in theory but unsustainable in practice and one that could drive away the very providers who make person-centred care possible.